Is there room for hydrogen fueled ICEs? Our interview with Alastair Hayfield (Interact Analysis)

«Our research shows that, whilst the technology clearly has the potential to reduce carbon emissions, the use of hydrogen combustion engines in heavy duty applications will be limited because of the challenges with machine and fuel price, the small number of suitable applications, and the shift toward battery and fuel cell solutions in many other applications».

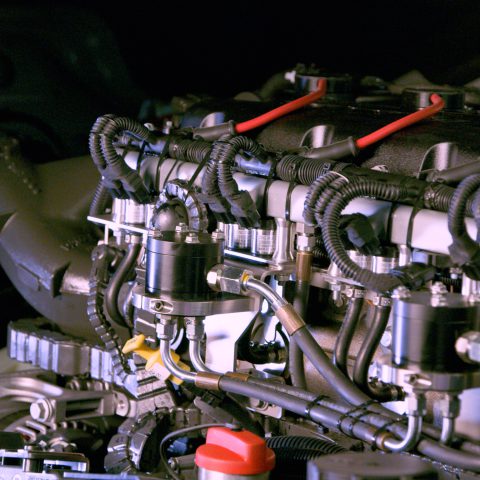

Is there room for hydrogen fueled ICEs in the commercial vehicle sector (and not only there)? Alastair Hayfield, Senior Research Director at Interact Analysis, wrote a very interesting and thorough article, whose full version can be found here. «A hydrogen fueled combustion engine works in much the same way as a diesel fueled combustion engine», he wrote. «Hydrogen is combusted to produce water with no carbon-based emissions; however, the temperature of the reaction produces nitrogen oxides, which are harmful to human health. Whilst these emissions can be minimized by controlling the combustion process or aftertreatments, they can never be completely removed, and the control process adds costs to the engine».

Hydrogen fueled ICEs vs conventional ICEs

Besides, «In addition to emissions and the costs associated with minimizing them, a ‘regular’ combustion engine designed to use diesel needs to be modified to run on hydrogen, adding further cost. Additionally, a weighty set of high-pressure hydrogen tanks must be added to the vehicle, further increasing cost and decreasing the cargo payload». There’s surely more to say about the current cost of hydrogen and its trend in the near future, as well as about the comparison with battery electric powertrains, which are currently quite expensive to produce and maintain. There is also the issue – we read in the article – of where the hydrogen comes from, which is closely related to the ‘color’ of hydrogen.

The hydrogen engine is more expensive and the actual hydrogen is expensive. It is very difficult for an operator or an end user to choose a vehicle that is more expensive and less efficient

Alastair Hayfield, Senior Research Director at Interact Analysis

In a scenario featured by pros and cons about the suitability of hydrogen fueled internal combustion engines, as well as by several uncertainties related to possible applications and technological challenges, Alastair Hayfield summarizes at the end: «Our research shows that, whilst the technology clearly has the potential to reduce carbon emissions, the use of hydrogen combustion engines in heavy duty applications will be limited because of the challenges with machine and fuel price, the small number of suitable applications, and the shift toward battery and fuel cell solutions in many other applications». We wanted to go further and had a very pleasant conversation with him, starting from the legacy of the COP26.

«A long-term trend»

Mr Hayfield, after the COP26, what’s your opinion about the internal combustion engine fueled by hydrogen as a transition technology?

«I think it can work, but there are some challenges to face. All the manufacturers and OEMs will have to develop their engines, road test them and it will take time. We won’t see their engines rolling out of production in 2022, it’s more a long-term trend. Realistically, it will take at least three years before this technology enters the market in meaningful volumes. However, we have to face the challenge of NOx emissions. I wonder if this technology will be overtaken by other solutions, i.e. fuel cells. Also, some think hydrogen doesn’t pollute but at the moment most hydrogen is not green, it’s brown and there’s still a carbon footprint associated with it. For me, there are still many issues to be resolved in this technology that sounds very promising: there are technical challenges and market challenges that make this technology more suitable to remain kind of a niche».

You mentioned green hydrogen, which can be considered the key to a really sustainable transition. How far are we from the development of green hydrogen on large scale in the commercial vehicle sector? Our impression is that we are still quite far from green hydrogen.

«I agree. If we look at Australia or the Middle East, we see some serious investments going towards green hydrogen, but I think it’s going to take a long time, not until 2025 or further».

All the truck manufacturers talk about long-term strategies: biodiesel, electrification, fuel cell. They hardly speak of hydrogen at all, except some exceptions. In your opinion, are they doing tests without communicating it or are they more focused on fuel cells?

«I think they are more focused on fuel cells and battery electric, if you look where almost all of the investments are going: billions of euros are going to battery cell production. I think there’s very little additional money for alternative solutions. Almost all on-highway truck manufacturers are focused on battery electric. Obviously, Cummins is doing some work around hydrogen in internal combustion engines. They have two models available and supplied in North America in a path towards positive perception of hydrogen used in internal combustion engines. Cummins have invested a lot in hydrogen, but I think in Europe this is not the best solution».

Concerns and costs

In Europe, some politicians are scared about electrification because it could cost much to the whole supply chain, because we have a lot of components manufacturers involved in the traditional powertrain systems. Do you think this could be an obstacle to research about electrification or new technologies?

«If you look at jobs in the automotive industry, passenger cars, commercial vehicles, off-highway, a large number of jobs has nothing to do with powertrain: you still have to assemble vehicles, you still have to produce lighting, braking, interiors, infotainment systems, etc. Here in the UK, there was a lot of concern that Ford would shut its Halewood transmission facility, but they have just announced they will reinvest £230m funds into producing electrified components. I think this is an opportunity to rescale, to reinvest. I don’t really agree with the argument this is going to cost a lot of unemployment or that this is really bad for the supply chain».

I think truck manufacturers are more focused on fuel cells and battery electric, if you look where almost all of the investment money is going: billions of Euros are going to battery cell production

Alastair Hayfield, Senior Research Director at Interact Analysis

Can hydrogen ICE and fuel cells coexist in the future?

«I think so. I think hydrogen ICE is a transitional technology, and I don’t see it becoming a major part of the market in a long term».

Two key issues: efficiency and infrastructure

Converting internal combustion engines to hydrogen may imply a loss in efficiency?

«If you compare a Diesel internal combustion engine with a hydrogen one, theoretically the hydrogen engine should be thermally as efficient. In reality, it isn’t, because obviously we’re looking to a hundred-year story of investment in diesel to make it as efficient as possible. Actually, it isn’t so. Then, we have another problem: the hydrogen engine is more expensive and the actual hydrogen is expensive. It is very difficult for an operator or an end user to choose a vehicle that is more expensive and less efficient. With fuel cells, the powertrain is much more efficient than any form of internal combustion engine. Several manufacturers have been quite slow in the transition to electrification because they don’t have money to invest, so I think they could partner to develop solutions. Brown hydrogen technology is technically feasible, but I wonder how quickly they can scale this technology from the cost perspective, but the investments are going to green hydrogen, so I don’t think it will be in the short or mid-term».

A crucial issue is the infrastructure, which is a problem for hydrogen ICEs but also for fuel cells…

«The problem is basically the same: how do you transport hydrogen around the world? My opinion is that it should be converted into ammonia, transported by ship and then converted back from ammonia into hydrogen. But if we are talking about local distribution, that’s very challenging because hydrogen storage is very expensive and it is unlikely to be stored in the next few years in remote areas or outside the big cities. If you’re going to use hydrogen in internal combustion engines in agriculture or in mining equipment, I can say this can be achieved. But, how can you get this fuel to where is needed? This is the real challenge. That’s why I think it’s a quite limited technology».